“Exceptional times call for exceptional measures”, or so the mantra goes these days. The Great Lockdown has lead us to close ourselves in our own homes – but has also locked away many of our civil and political rights, such as the freedom of assembly or the normal functioning of parliamentary systems.

Not that quarantine measures aren’t justified, when the choice is between temporary containment or widespread viral contagion. Laws and norms – the constitutional-legal order of a society – are set for those circumstances the legislator can foresee. Contrary to a war, which still requires a formal declaration at a definite point in time, a global pandemic does not abide by the principles of international law – how could it? – and hits without warning.

The state of exception

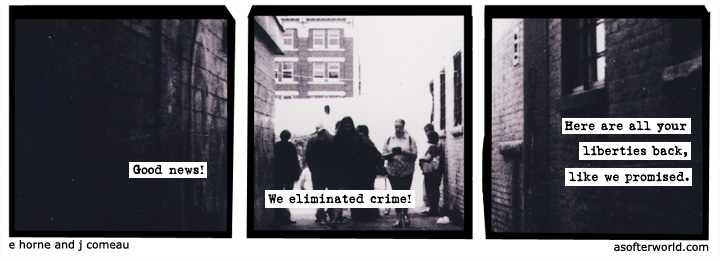

A crisis of such magnitude, then, naturally calls for urgent and forceful actions in response. For such actions to be undertaken, the Executive branch of government requires to wield emergency powers, which are provided for in most, if not all, modern constitutions. Farsighted constitutional forefathers, who had just lived through the horrors of fascist authoritarian regimes and the Second World War, rightfully delineated the reach and duration of such “State of exception” provisions. They sought to establish, in the words of German philosopher Carl Schmitt [1], the conditions for and constraints on a “commissarial dictatorship”: a momentary suspension of the constitutional order aimed at preserving the constitutional order itself. And yet, as later philosophers rightfully remarked,[2] who’s to say that the “sovereign” – he who wields emergency powers during a state of exception – would return them once the crisis passes?

Emergency measures in the EU

Elements of a “state of exception” can be found in the European response to the COVID-19 outbreak. Forget the usual “bad kids on the block”, Hungary and Poland: ruling-by-decree, the suspension of elections and parliaments’ sessions, restrictions to personal freedoms, have become the norm across Member States. Measures that are justified – and rightly so – by the need to protect the inviolable right to life of citizens. Discomfort has, however, began to surface. In Spain, the contention over the state of emergency could be dictated by the opportunity to exploit the structural weakness of a minority Government for short-term electoral gains. But partisan political interest can’t always be the excuse.

It is the right of Parliaments to oversee and the duty of the oppositions – as extremist and filthy their policy proposal may be – to question the actions of Governments. In Italy, the country I know best, the confinement measures have largely been decided by Prime Ministerial decrees, administrative acts with “the power law”, which however crucially lack in parliamentary oversight. They have been preferred – for reasons unknown – to other instruments foreseen in the Italian Constitution, which are equally time-bound and that the Government can adopt autonomously, such as law-decrees and legislative decrees. These must be converted into law at a later stage, which allows then for ex-post parliamentary oversight.

The question, rather than whether such measures are momentarily justified, is to whether the precedents we are setting today will stick around after the health crisis. The state of exception is, in fact, the Hotel California of modern democracies: you may “check out anytime [you] like / but [you] can never leave”.

A state of permanent emergency

Western politics has been living in a state of permanent emergency for the past two decades, and emergency-like powers have been used without restraint also in times of peace. Under the guise of ensuring swift legislative processes at EU level, most EU legislation has in the past decade effectively neglected the Treaty-mandated processes in favour of the so-called “trilogues”: informal (and thus untransparent) negotiations between the Commission, Council and Parliament on legislative texts. It wouldn’t be unconceivable to consider this a mild – yet persistent – version of the Schmittian state of exception.

Let us be very clear: the Commission (as the EU’s executive) could hardly ever become an authoritarian institution, not least because it is not “sovereign”: it lacks the competences and the tools to assume the emergency powers required to unilaterally impose its will, with all due respect to those who lose their Eurosceptic voices shouting the opposite. As federalists, this is part of our fundamental battle: that no level of Government – local, regional, national, European, global – be ever “sovereign” in the Schmittian sense, able to indefinitely suspend the constitutional order and the rights of its citizens.

Therein also lies the strength and weakness of parliamentary democracies. Parliamentary and judicial processes are slow-by-design, as they are set to distil the elements of a decision to allow for their careful consideration and a well-informed public debate.[3] Decisions taken in secluded, smoke-free rooms are undoubtedly swift, but they will hardly reinforce citizens’ confidence in the EU. Can decisions taken in a permanent state of exception, with an eye to the next electoral round, rather than the next generation, really prepare us for the deep and structural changes of the world to come?

The struggle ahead

As some of us edge towards the end of our COVID-19 lockdown period, many questions have surfaced as to how we will slowly return to our previous live: work outside our homes, maintaining social distancing, how we will deal with and pay for the prolonged recession that will outlast an otherwise relatively short-lived (yet not less severe) health crisis. But the question very few seem to ask is that of how we will deal with the lasting effects of the pandemic crisis on our democracies.

A fraught citizenry is easily seduced by the illusions of governmental grandeur: the firm wooden desks from whence quarantines are announced, on a background of golden tapestries and governmental insignias, the subtle suggestion that the Executive is, and will always be, a well-meaning and kind protector - and that, dear reader, is far from certain. A feeble voice in the back of your head is trying to draw attention to the flipside of this situation: read out in the same monotonous voice of the same Prime Minister, it’s a statement that democratic checks and balances have, for now, ceased to apply - and that, dear reader, is the truth.

Oh, emergencies are a beguilling call to absolutism, and the powerful are addicted to the sweet pitch of these sirens. That which starts sweet ends bitter, and that which starts bitter doesn’t always end sweet. That is why we should cherish parliamentary democracy and its slow processes; and that is also why we cannot give up on our struggle as radical democrats and federalists.

Follow the comments: |

|