The major European party alliances, like the European People’s Party (EPP), Party of European Socialists (PES), Alliance of Conservatives and Reformists in Europe (ACRE) or Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Party (ALDE), have its members, associate members and observers from non-EU members European parties. Political parties from the EaP countries often align themselves with pan-European political groups.

While usually parties across the EU join particular groups based on ideological principles, in the case of EaP countries these linkages are not that clear. Such alliances are not usually based on ideological similarities. By affiliating themselves with pan-European groups, EaP political parties are primarily concerned with gaining ground in internal politics. Patronage networks and alliances built within pan-European unions are often used for gaining concessions in national politics. At the same time, Europarties seek to maximise their influence and prestige outside the EU.

Personality-oriented party relationships

The scale of the current relationship between Europarties and political parties from EaP may be minimal. However, there is room for a vibrant and intense relationship. Cooperation from both ends is more influenced by “pragmatic reasons”, rather than ideological and policy proximity. The relationship between European political parties and parties from the EaP are mostly built on personal relationships between local party leaders and Europarties, thus forming into “personality-oriented party politics that are embedded in clientelist relationships and oligarchic business circles”.

The largest, “pro-regime parties of the EU political system”– EPP, PES and ALDE – pursue their pragmatic goals while collaborating with parties from EaP: facilitating EU strategic goals and common foreign policy. Angelos Chryssogelos, a scholar in this field, argues that is the reason why mainstream parties are active in the EaP and Eurosceptic and parties with “little external reach” usually avoid such consistent institutional collaboration with parties outside the EU. While being traditionally fiscal conservative, EPP has collaborated with “catch-all” populist parties, like United National Movement (UNM) in 2004-2012 in Georgia. Major partners of PES in EaP countries have ties, or at least have cooperated with, formally left-wing, but oligarch-driven parties. In Moldova, PES affiliated itself with the Democratic Party led by a controversial business tycoon Vlad Plahotniuc, while the Georgian Dream party has been established and led by a wealthy businessperson Bidzina Ivanishvili.

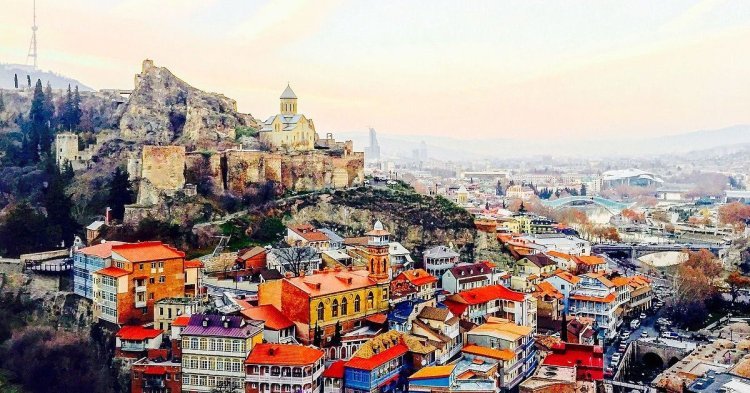

Georgia: Unintended left-right division

Out of six EaP countries, Georgian political parties are arguably among the most involved in the European party politics. Mainstream political parties are members of EPP, PES and ALDE. Current and former ruling parties align with the two biggest party unions: former ruling party UNM and its splinter Movement for Liberty–European Georgia (MLEG) align themselves with EPP, while current ruling party – the Georgian Dream – has been affiliated with PES. At the same time, minor liberal political parties, like the Free Democrats and the Republican Party of Georgia are members of ALDE.

In their discussions of the motivations behind transnational party cooperation in the case of Georgia, scholars have identified them as pragmatic: while parties at the European level try to expand their influence and gain additional supporters, Georgian parties try to pursue their internal political agendas, often manifested as brawl against rival parties. A vivid example of such conflict is the case of Gigi Tsereteli’s election of as President of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCEPA). Eventually the representative of the oppositional MLEG party was elected as President, even though in 2016 the ruling GD party had said it did not support his candidacy as it ‘could cast a shadow on objective and balanced perception of the OSCE mission results during elections’. Moreover, there are even more vivid examples when Europarties participate in internal Georgian political affairs: EPP facilitated the agreement between MLEG and UNM to cooperate during the upcoming presidential elections in October 2018.

Ukraine: Skewed towards the right and centre-right parties

In the case of Ukraine, parties that align themselves with European-level parties are predominantly associated with centre-right and right-wing party unions. It is believed that many left-wing parties that could have potentially be part of left-leaning party unions have been largely discredited and lost popular support after the Euromaidan events. In addition, the PES President’s statement during Euromaidan did not contribute to close relations between European socialists and dominant political parties that took leadership in Ukraine in the post-Yanukovych period. Parties that have a significant European affiliation, both in government (Petro Poroshenko Bloc “Solidarity”), and in opposition (All-Ukrainian Union “Fatherland”), have ties with EPP. However, the major criteria for EPP’s collaboration with its Ukrainian sister parties are their popular support and whether the party supports a “pro-European choice” for Ukraine. As for the Ukrainian parties, it is the tool for internal and external legitimacy.

Nevertheless, there is still room for other European political parties to be involved in Ukrainian politics. ALDE cooperates with Civil Position and the European Party of Ukraine, though there are no mainstream political unions in the Ukraine. PES should also activate its presence in the Ukrainian party politics: although there are no major centre-left parties, the general mistrust and low support for political parties means there is a big opportunity for new political actors to enter Ukrainian political life.

Moldova: diverse, but politically unstable

Moldovan political parties are largely present on a wider political and ideological spectrum of pan-European party unions. The reason could be the greater ideological diversity of mainstream Moldovan political parties. Having a pluralistic, albeit unstable political spectrum makes the Moldovan party system very difficult to predict. Political and declared ideological diversity does not constrain Moldovan political parties from collaborating and forming governmental coalitions that can be resisted by the European sister parties. In order to secure power, EPP member Liberal Democratic Party of Moldova (PLDM) have often been collaborating with political parties that were against Moldova’s pro-European integration, which has been firmly criticised by the European partners of PLDM.

In contrast to Georgia, where major Europarties support two different camps of national-level political parties, in Moldova major Europarties unanimously support a specific type of political parties in order to form pro-European government after the elections. The most vivid exception would be the Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova who are a member of the European Left. However, the corruption scandal involving one of the prominent pro-European politicians, Vlad Filat, and the election of the pro-Russian Igor Dodon as President of the Republic have left a negative footprint for the pro-European future of Moldova.

Europeanisation or joining the prestigious club?

In general, the integration of parties across post-Soviet and post-communist Europe in the milieu of Western party politics was implemented in the name of Europeanisation. However, it is believed that this process only had “cosmetic” impact and parties did not change their initial organisational structure, policy formulation, or political behavior that were formed during the late 1980s and early 1990s. As political parties in the post-communist world usually lack a coherent ideology, seeking closer ties with pan-European parties has been dictated through opportunism rather than ideological affiliations. Exploring this topic in her book, political scientist Maria Shagina describes cooperation between Europarties and parties in Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine something like joining the prestigious club. Though it had unintended consequences, like penetration of EU norms and values, still the initial factors were internal political agendas. In general, the process was driven by narrow goals of different interest groups and had more emphasis on personal relations between decision-makers, rather than communion on shared values.

Follow the comments: |

|